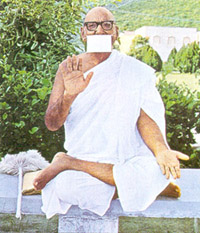

Scripturs Guide Life:- By Upadhyaya Amar Muni

|

Scripturs Guide Life

By Upadhyaya Amar Muni

Scriptures are the voice of the Realised Souls and the foundations of our faith. However; the religious history of the world tells us that no venerable One has ever written any scriptures himself. Whatever is in the sacred texts has been handed down to us through the oral tradition. The words of the masters have then been written down, and in the process the writers have excluded some if the teachings, and added some thoughts if their own. The works so compiled were accepted as scriptures, and became the focus of human faith. These interpolated passages could not qualify as the truth, and so some if the facts expounded in the scriptures have lost their credibility. But because the scriptures are the object if our faith, the dilemma remains as to whether we can deny or doubt in any way the facts contained in them. There are many things written in the scriptures. Who will make the distinction between the words if the prophets, and the additions or interpolations, and how is it to be done? This all-important, but most difficult task, can be accomplished only by one who is coloured to the core by faith in the venerable Ones, whose transcendental wisdom is one with the truth, and whose finely-honed vision can penetrate the outer trappings of words and touch upon their innermost meaning. Gurudev Shri Amar Muniji clearly possessed all these qualities. By means of his extraordinary intellect, he carried out the praiseworthy task of discerning the voice of Tirthankar Mahavir among the words of the scriptures that to date had commanded people's total faith, and presented the revered words to us. He established the validity of the scriptures by daring to remove the interpolations from them. The arguments he used to distinguish between the scriptures and the other commonplace compilations are presented in the following pages: Religion and science both pose profound questions for mankind. Both are intrinsic to our lives, yet the have been cast in distinctly separate roles, Today, religion is arbitrarily tied to certain specific rituals and customary belief, whereas science is restricted to material research and the superficial analysis of the universe. The Limiting of thought processes pervades both spheres, with the result that they have become mutually antagonistic. Today's religious men say science is false, and in turn science is mercilessly decrying the beliefs and observances of religion. The True Scope of Science and Religion : I believe that the agitation and distress in the minds of the religious today, this flood of dissatisfaction and doubt about the scriptures, is caused by restrictions placed on their thanking. The cling to age-old orthodox ideas, and consider any compilation of an ancient language as scripture and therefore representative of religion. The devout are neither able to appropriately analyse these books intellectually, nor are they able to give up their attachment to them. They are bound by conventional beliefs and some oft-repeated traditions, and have become narrow-minded. It is this prejudice that causes all their doubts and discontent. When talking of the scriptures, we must first understand that science and religion, unlike Rama and Ravana, are not rivals. Both are sciences: one of nature, the other of the soul. Religion, which is a spiritual science, involves the study of the pure and impure forms of the soul, its liberation and bondage, and the growth and decay of its sacred and sinful states. Natural science, as I feel it should be called looks at nature and penetrates its secret processes. It also includes the study of the protection, nourishment and treatment of our body, mind and senses. Both are related to the indivisible and indestructible existence of life. One touches on the outer man, the other concerns itself with his inner being. The field of spiritual science explores the inner consciousness and the substance of the soul. Natural science includes the experimental study of nature and research into it right from the microscopic atom to the vastness of galaxies. Natural science is thus knowledge of the external world, and spiritual science, which deals with the purification and sublimation of the soul, is the knowing of the inner world. From this viewpoint, natural science and spiritual science are not in competition with each other, but altogether complementary. Science is experiment, where religion is reflection. Science unveils the mystery of the wondrous powers of nature and establishes their existence by experimentation. Spiritual science lends us the wisdom for their constructive utilisation. It also opens up the mind to higher thinking and expunges our consciousness of animosity, baseness and fear. It decides when, where and how scientific discovery should be used. It is spiritual science which provides natural science with a discerning vision. How then can anyone say that natural science and spiritual science stand opposed? Life today cannot just be involved in the aspiration of the soul, neither can it be wholly taken up with the progress of the external self. Life has two aspects, the inward and the outward. Life is about maintaining the right balance between the two and moving forward. Inner wisdom is necessary so as to avoid division and indiscipline in the outer life. The inner life too is dependent on the outer life for the care of their common vehicle, the body. The material and the spiritual can never be mutually exclusive. On the contrary, a qualitative as well as quantitative value should be given to both in order for us to progress. Only then can life be beautiful, useful and blissful. When I think along these lines, it seems that natural science and spiritual science are both an integral part of life and, therefore, there can be no question bf conflict or contradiction between them. Today, several beliefs based on religious texts clash with the discoveries of modern science. These beliefs are being called into question and believers are caught in a whirlpool of doubt. So how can we suddenly set aside the age-old religious texts and at the same time brace ourselves for the task of decrying the findings of science? It is this war of ideas that has led to chaos in the field of religion. Wherever age-old conservatism and rigid irrational beliefs triumph, science is seen as false, illusionary and cataclysmic. It is because of this misconception, I believe, that science is assumed to be the opponent of religion, and it is due to the prejudices of religious people and their hatred for anything scientific, that radical modern thinkers have called religion the opiate of the masses - an agent of hypocrisy and falsehood. If we try to examine the matter more fairly, the reason why scientific discoveries are at odds with religious beliefs will become obvious. In this context we ought to be clear about two things: Firstly, the definition, purpose, and subject matter of the scriptures. Secondly, should we consider whether the Smritis, Puranas, Jain-Sutras and other reference books that go by that name are true to the letter or not. Books as Scriptures : The first and foremost thing to grasp is that the word 'scripture' is a sacred term, and its influence extensive. By comparison, a book, a treatise or a commentary dealing with religious matters, is much less significant. Some dictionaries may call the two words synonymous, but grammatically they are not. No word can ever be an exact synonym for another; there is always a basic difference in meaning. With this in mind I think of 'book' and 'scripture' as two entirely different words. The scriptures are essentially expressions of the experience of ultimate reality, consisting of sat yam (truth), shivam (well-being), and sundaram (beauty). A book may not necessarily contain this affirmation of the mobilisation and materialisation of personal and universal welfare. Scriptures are a guide to the perception and performance of the truth, whereas the subject matter of a book is at one remove. Once we learn the difference between the genuine scriptures and other books about religious matters, science and religion will no longer be at loggerheads. One discipline will not dub the other false or 'all-destroying'. While the intelligentsia shows great indifference towards religious texts, whether Jain - Sutras, Smritis, or Puranas, the devout today also view them with some doubt. The reason lies in our failure to differentiate between books and scriptures or understand the real meaning and worthiness of the latter. We have accepted as scriptures each and every ancient text available in Sanskrit and Prakrit; we have simply lumped them all together, calling them the voice of the Lord. Tying them around our necks like a millstone, we have proclaimed them our sacred texts and, as a consequence, the unchanging truth. We call anyone who speaks against them a liar or an ignoramus. This irrational attitude towards books on religious matters has gripped not only India but the entire religious world. This has been the case for a long time. One can still read about how the adherence of some people to books they called sacred, forced scientists, who dared to question these works, to leave the country. The pages of history are filled with stories of scientists executed for having had the temerity to refute some of the contents of these books. Books Are Mere Compilations : Those books which are not scriptures, but have come to be thought sacred over the years, have caused great confusion amongst all sorts of religious groups. Granth-the word for 'book' in Sanskrit is etymologically related to the word granthi, which means 'knot'. A Jain monk or ascetic is known as nirgranth, as there is no knot or binding within him which might hold back the infinite welling up of love, forgiveness, and universal compassion from the depths of his inner being. A knot is tied when things have to be collected or bound together. Some things taken from here, some things taken from there, are then tied together and joined or yoked. It is through this same type of collection and binding together that some 'holy books' come into being. The sense that the word granth conveys is also found in the Hindi verb gunthana, which means plaited together. When a gardener makes a garland, he knots flowers together on a thread or a piece of string. First, he picks up a flower, ties it to the thread, and next he ties a knot. Then he takes up another flower, threads it, ties another knot after it, and so on until the garland is ready. Similarly, a book is a garland of thoughts strung and tied together. Without knots there is no garland. In the same way a granth will not be prepared without knotting the collected thoughts together. This implies that a granth or book does not necessarily require original thought; it is more a compilation or a compendium, a string of thoughts and beliefs. The same is not true in the case of genuine scripture. Scripture: Truth's Witness : The scriptures are based upon truth that is self-evident. Truth always touches the consciousness of humanity as a whole, and in our culture, truth is always coupled with welfare. So the vision of truth also reflects a picture of the lifting of the consciousness of the entire universe. Though the material sciences also unveil the truth, they do it from a purely intellectual standpoint. It is not founded on experience of the exaltation of human consciousness, so I do not include it in the realm of scripture. We are also of the opinion that scriptures are the voice of the sages and seers. Yask has defined the word seer as rsuh darsanat38, which means the seer envisions and experiences the truth. However, not every ascetic is a seer. Only he who can vividly experience the truth by means of his rationally refined knowledge and his piercing wisdom is a seer in the real sense. The Vedas, therefore, depict a seer as a singer of truth. According to the Vedic and the Jain traditions, sagacious speech (arsa vani reveals first-hand knowledge which elucidates and establishes the existence of godhead on the basis of an actual experience of the truth. The preacher of true scripture never imparts knowledge borrowed from others. Such knowledge does not encompass the welfare of all. His benevolent teachings spring from the flow of pure knowledge which wells up from within and comes directly from a pure soul. The principle theme of a seer's teachings is to eliminate the impurities of the soul and reveal its light in the form of infinite knowledge and infinite vision. When that great scriptural expert of the Jain tradition, Acharya Jinabhadra Gani Kshamashraman, was asked what works could be called scriptures, he said, 'That through which knowledge of the real truth is perceived, which disciplines and enlightens the soul, should be called scripture.' 39 The word shastra (scripture) in Sanskrit is derived from the root word shas, which means to govern, instruct or enlighten. So shastra implies an essence of reality that educates, governs and enlightens the soul. This definition is not some kind of imagining on the part of the Acharya - it is firmly based in the Jain Agamas. Even the voice of Tirthankar Mahavir comes to us clearly through the Agamas: A scripture is that which awakens the soul and leads it to an active involvement in the performance of tapa, kshama, and ahimsa. The third chapter of the UttaradhyayanSutra, which is considered to be the final message from Tirthankar Mahavir, states that there are four things which are most rare and extremely difficult to attain: manusattam sui saddha sanjamammi ya viriyam40 'human birth, truly listening to the scriptures, faith, and a conscious working towards selfcontrol'. Later on in the text, the definition of scripture is given as: jam socca padivajjanti tavam khantimahimsayam41 'scripture is that which disciplines the aspirant's mind and awakens in him a feeling for practicing tapa'. It results in controlling the impetus of wildly scattered untamed desires. The control of these desires paves the way for abstinence and lends momentum to the journey along the path of forgiveness. In this context, I would like to add that the word khanti - forgiveness - has a broader meaning. Forgiveness is not limited to the quashing of anger alone, but includes the prohibiting and falling away of all passions. Only he who can rid himself of anger, ego, deceit and greed, is truly kshamavan forgiving. Another meaning of the Sanskrit word kshama is 'proficient'. Someone who is capable of overcoming his passions, can conquer evil inclinations like anger and selfimportance, and keep his mind ever tranquil, is kshamavan. The Aim of the Scriptures: Welfare for All : Ahimsa, along with the practice of kshama (forgiveness) and tapa (penance), is one of the factors that is woven into the fabric of all the scriptures, and by this inclusion, the desire for the well-being of all sentient beings is implicit. Tirthankar Mahavir has called ahimsa 'a goddess' (bhagavati)42 That famous master of scriptural knowledge, Acharya Samantbhadra, has called ahimsa 'the greatest God43 . This means ahimsa in its pure form is an all-embracing spiritual concept and is the propitious harbinger of well-being for all. To practice ahimsa is an endeavour to establish welfare for all in the world. Compassion, gentleness, selfless service, co-operation, friendship and fearlessness are all different forms of ahimsa. The scriptures can be defined as containing a philosophy or essence of reality which heals life and cleanses the soul through the practice of tapa, kshama, and ahimsa. The Purpose of the Scriptures : By understanding the definition of scripture, we understand its purpose. In this context Arya Sudharma Swami, the successor to Tirthankar Mahavir, said, 'savvajaga-jivarakkhana-dayathtayee bhagavaya pavayanam sukahiya - 'The Tirthankars preach sermons for the well-being of the entire world, with the intent of compassion and the security for all creatures at their core' these are the scriptures. Sometimes the definition and purpose of something might be one and the same thing, sometimes they may be separate. Here the purpose clearly lies in the definition. Though the definition itself clarifies the purpose of the scriptures, yet the separate description of the purpose emphasises the fact that the true aim of scripture is to open up the path of universal welfare. This common aim of the scriptures is accepted by Jains, Buddhists and the Vedic religion alike. Even Christians and Mohammedans say that Christ and the prophet Mohammad Saheb brought a message oflove and mutual harmony for all. I feel that this singular purpose of the scriptures is so all-pervasive and all-encompassing that it cannot be challenged by any philosopher or any thinker of standing. When Acharya Haribhadra, the great luminary of the world of the Jain Agamas, was confronted with the question about the purpose of scripture, he too repeated, 'Just as water washes all the dirt out of clothing and leaves it shining and clean, so too scripture washes away the filth of all passions like lust, anger, greed and jealousy from the mind and leaves it pure and clean.' 45 Thus, scripture is that essence of reality from which one obtains the knowledge of the self and progresses towards 'pure-being' through practice of self-discipline and ahimsa. The So-Called Scriptures : The definition of scripture, as described in the paragraphs above, is in itself a science, a truth. Can science ever contradict science? Can truth ever challenge truth? No! No! One truth cannot refute another; if it does, then it is not the truth. So we must recognise that any holy book which can be challenged by human thought or empirical science is not genuine scripture. Be they the Jain Agamas, Shrutis, Smritis, the Buddhist Tripitakas, the Bible or even the Koran, they are compilations fostered in the name of scripture. I do not accept any thought or idea, be it old or new, without question. I cannot tolerate the blind acceptance of any granth (book) as the truth, even if it is called a Shastra, Shruti, or Smriti. Neither myself, nor any other independent thinker can stand for this tendency, especially when these so-called scriptures do not successfully pass the universally accepted test of being instrumental in promoting world welfare. Can those 'holy books' that call for animal slaughter 46 and human sacrifice in the name of religion 47, and raise barriers of hatred and hostility between man and man, ever be the genuine revelations of the sages - the seers of truth? In one so-called scripture, it is said about a shudra, who is a member of the human race: 'He is a living crematorium.48 One should even avoid his shadow.' 49 Does there seem to be any kind of humanity in teachings like this? Woman, who is exclusively granted the great and glorious privilege of motherhood, and who showers the entire human race with love and affection, is referred to in this way: 'There are no greater sinners than women.' 50 Can such statements ever be part of any religion? When these books, sowing the seeds of class conflict, cast-antipathy, and communal hatred - so breaking up human consciousness into many fragments proclaimed: 'On being touched by any member of a certain sect, one must immediately plunge into water with all one's clothes on' 51, did they show a sign of any self-knowledge? A sage is a seer and a thinker - one who himself sees the real truth and reflects on it. He experiences with all creatures the 'oneness' of an all-pervading consciousness. Can such a sage or muni, ever utter such malicious or divisive words? Can it be in accordance with the sanctity of scriptures like the Vedas, Agamas, and Tripitakas, that on the one hand, those same sages or munis who preached the scriptures taught amity, and then on the other, they are said to have taught hatred to humankind? In fact it is inappropriate to consider as scripture any ideas, interpolations, or writings by any scholar from the Middle Ages, be it in Sanskrit, Prakrit, or any other language, and become bogged down in it. I have great regard for the distinctive thought and vision contained in those texts, as I do for their message of universal welfare. I myself read them and preach their ideas. However, I think that it is not right to follow some kind of narrow-minded intellectual tendency to consider these writings to be always true to the letter. Compilation of the Agamas in the Later Ages : As far as truth is concerned I have never been bound any particular philosophy. I have always supported liberal and independent thinking. So I do not hesitate to comment on the Jain texts from the same critical point of view that I would adopt towards Vedic literature. Being a student of history, I accept the fact that every religious tradition undergoes changes from time to time, and in the process some false ideas creep in among the true ones. However when the right time comes along, these thoughts are refined as well. At present, I have before me a long list of different opinions regarding the beliefs and structure of the Jain canons. Some of the history is now available for us to look at when, where and how these beliefs were changed, how many of the new ideas were accepted, and how many of the old ones were rejected. The Nandi Sutra, which we include as an Agama and hold to be a revelation of the Tirthankar, was in fact compiled a long time after Tirthankar Mahavir's nirvana. It was either written or compiled by Acharya Devavachak. In the lengthy period between the time of Tirthankar Mahavir and that of Acharya Devavachak, there were many major upheavals in the country. There was a saga of famine, political revolution, and rapid change, growth and reaffirmation in all the religious traditions. Yet we accept these sutras, compiled 1,000 years after the nirvana of Mahavir, and all the facts mentioned in them, as the voice of a. Tirthankar. Though much of these later Agamas touch upon the enhancement of life, I am certain they are not directly connected with the actual revelations of Tirthankar Mahavir. Everyone admits today that much of the original teaching has been lost because of gaps in the system of oral transmission, or the fact that memory is weak. Why then can people not admit that some contemporary beliefs must have been added to the texts at certain points in the' compilations. Today we ought to think about this subject in an entirely new way. We should assess truth on the basis of reality. As one separates milk from water, we ought to separate the words of Tirthankar Mahavir from those works compiled by scholars in the later ages. We must have courage to do this today, for if we hesitate or shy away, the truth will be concealed from us. Our new age of rationality demands a decisive answer, and this answer will have to be provided by all who are well-versed in the scriptures. I wonder whether you will ever be able to prevent Mahavir's omniscience from being invalidated, when even today you cling to the illusion that the texts which you recognise as scriptures are literally true in every respect. If we want to safeguard the validity of Mahavir's omniscience, we need to ascertain in a discriminating way which parts of the scriptural works are the words of Mahavir i.e. the real form of the scriptures. If we fail, the generations to come will question Mahavir's omniscience. Sort out the Scriptures : The question you may ask is who are we to sort through the scriptures and separate from them the voice of Mahavir. What right do we have to decide on the subject matter of the scriptures, or judge what is truly scriptural and what is not? My reply to this is that we are the heirs of Mahavir; his glory fills our hearts. Under no circumstances can we allow the name of Mahavir to be besmirched. We never did, nor can we ever, believe that Tirthankar Mahavir could preach a falsehood. I would say that whatever has been clearly proved false today or could at some stage be proved false, can never be a statement from a Tirthankar. Applying this same criteria, we can then sort out the Tirthankar's words from the so-called scriptures, then if anyone challenges these teachings, we can counteract their accusations with the truth. Shatter the Shackles of Inflexible Thought : Spiritual advancement in life does not depend on the number of scriptures or texts traditionally handed down to one's sect. The spiritual state of a person can be highly developed and elevated despite having only a few scriptures. The thought and vision required for spiritual development are both awakened from within. The more flexible and free one's attitude towards truth is, the more soul-orientated one's thinking, the greater will be one's spiritual development. I have found that a prejudice for, a sort of lust for scriptures and other holy books, has been formed in our minds. Warning against such bigotry, Acharya Shankar says in the Vivekchudamani: 'Lust for the scriptures, like the lust for physical pleasures and the lust for worldly honour will bar one from attaining real knowledge.' Acharya Hemchandra adds: drstiragastu papiyan durucchedyah satamapi-'achieving the truth is almost impossible for anyone whose passions obstruct his perception.' Every now and then, we talk about anekant, (the doctrine of manifold aspects), and syadvad (the doctrine of qualified assertion). These should not remain mere slogans like those used by contemporary politicians. They should so become part of our thinking, that our perception of the truth will be unhindered and independent. Until such times as we get rid of our old prejudices and the obstructions to our vision built by blind faith, we will not be able to make the right decisions. Present circumstances demand that we break free of bigotry and begin to think in new ways. In this quest, our own wisdom is the touchstone. Tirthankar Mahavir and Ganadhar Gautam, who themselves were ardent seekers and seers of the truth, have both made it clear that your own wisdom is the only yardstick against which you can measure the real truth, saying: paf}f}8. samikkhae dhammaf!7 52 - 'religion or the intrinsic truth can be analysed only through wisdom, and truth can be judged only by the means of wisdom.' Evaluation of the Scriptures : The only method by which the scriptures can be truly examined is through the application of wisdom, and all scriptures should be subjected to its scrutiny. We have many companions who fear that such an examination will reveal that much of our 'gold' is actually brass. I would like to ask them why they are so worried; why they want to slink away from this examination. If something is gold, it will always be gold. If it is brass, how long will its coating of gold last in any case? In separating the gold from the brass, in setting the truth apart from all else, lies the magic of wisdom. That great commentator on the Jain Agamas, Acharya Abhaydev, in his commentary on the Bhagavati-Sutra, has laid down an important principle that could serve as a test for finding the true voice of Mahavir. He asks the following questions: Who could be called a Realised Soul or a Venerated One? What could be called the revelation of a Tirthankar? What is divine preaching? In reply, he says that Tirthankars preach only that truth which is an aspect of liberation, and a means to it. They do not preach anything that has no immediate bearing on the liberation of the soul. Had they done so, their own omniscience could not have been called so.53 This is a true touchstone for judging the genuineness of the scriptures that Acharya Abhaydev has presented to us. Before him the great logician of the fifth century, Acharya Siddhasen, who established Jain ontology on a par with other schools of philosophy, also propounded a decisive means of examining scriptures. He said, 'That is true scripture which contains knowledge experienced and examined by the Realised Ones, that cannot be displaced by the words of others, that establishes a principle which cannot be invalidated by argument or other evidence, that is beneficial as an instrument for the universal welfare of all creatures, and that resists ideologies opposing spiritual aspirations.'54 This method of examining scripture given to us by the Acharya is still valid today. When Kapil, the great philosopher of the Vedic tradition, and the great dialectician Gautam, included shabda - the Sanskrit for 'word' - as part of the authoritative testimony for judging a truth, they were asked which words would be acceptable as this authoritative testimony. To this they replied, 'The word of the Realised Ones is valid testimony.' The next question was, 'Who is an Apta (Realised One)?' They answered, 'An Apta is one who preaches the truth. He whose word is free of all contradiction, irrelevance, or irrationality is a Realised or Venerable One. Words that can neither counter, nor be invalidated by other testimonies, are revelations.' 55 The statement from the Acharya, quoted above, proves beyond doubt which words and whose words can be accepted as testimony to the truth. No matter how large or a reputable the book, do not ever accept as revelations of a Tirthankar, words in it that are not truthful, or that fail to stand the test of the truth. By so doing you prove your own genuineness, and the authenticity of the revelation. We should make the Decisions : I have discussed these finer points of logic so that we can awaken our intellect and decide for ourselves what scripture truly is, and what its purpose. Let us also conclude that those works, which are not in keeping with the definition and purpose we have just discussed, are not scriptures at all. They can be anything else - a compilation, a creative work, a treatise, or a book - but they cannot be called the revelation of a Tirthankar, nor can they be called scripture. According to the Uttaradhyayan-Sutra, only that literary work which inspires one towards the practice of kshama, tapa, and ahimsa, and thus awakens the soul, can be called scripture. This is such a sound and excellent method of testing. what the scriptures are that, if we use it as a yardstick to sort them out, we are bound to progress in the right direction. Whenever I have presented these views to fellow munis and other spiritual seekers, they have said, " What you say is true, but how can we say that we do not accept a particular Agama as scripture? If we did so, it would create havoc. Shravaks would lose their faith and our religion would suffer a setback". I am astonished at the cowardice of this timid and reactionary response. What sort of mentality do we have? We understand that something is true, but we cannot say so, for fear of what people might say! This slavish way of thinking, I believe, has toppled our ideals and destroyed our culture. This type of mindset has been responsible for the rise of skepticism and a resultant antipathy towards religion in our time. Devotion to Omniscience or Attachment to the Scriptures : It is horn scriptures that we gain knowledge of the supreme state of the soul. We are souls and a Tirthankar is a supreme and purified soul. The difference between a worldly soul and a supreme soul is only one of a degree of purity. Soul in its purest state is God. The essential nature of the supreme soul is not different from that of our own soul. Only those scriptures which enlighten us about our soul, show us the way to becoming a supreme soul, pave the way for purification and the perfection of our lives are true scriptures. These are the only ones we need. It is harmful to count those texts as scriptures that lead us to self-delusion and make us 'world orientated' instead of 'soul-orientated'. Such pseudo-scriptures distance us horn true faith, make our minds resdess with doubts, and provide others with an opportunity to mock our Tirthankars and our scriptures. If you look at things in an unbiased and objective manner, you may begin to wonder whether scriptures containing elaborate geographical and astronomical data, descriptions of the moon and the sun, of planets and constellations, or mountains and oceans can provide us with any inspiration for freeing ourselves from bondage. How do they show us the way to self-belief? What lessons of kshama, tapa, and ahimsa do we learn from them? Why should we consider those books, which have no relevance for our self-seeking consciousness and nothing to do with our aspirations towards purification, as our scriptures? On what basis should we accept them as the words, or even the teachings of the All-Knowing Ones? Many of the sacred books of the Jains, the Buddhists and the Hindus were compiled and revised during a period which stretched from a few centuries BC to 4th and 5th century AD. Whatever books were written in Sanskrit or Prakrit during that period were all included in the list of scriptures. The result was man's power to independently reason atrophied as he devoutly accepted every book as part of the scriptures, and everything written in them as a revelation of the Realised Ones. None of the Indian religious traditions has escaped this intellectual impairment. In the beginning this erroneous attitude may have gone unnoticed as they were blinkered by their devotion, but today its devastating effects are evident. The devotees of Indian religious traditions have become so entangled in these so-called scriptures that they are neither able to achieve anything with them, nor be wholly rid of them. My writing this is not intended as a repudiation of, or an insult to, the scriptures. We should understand and accept that scriptures differ from books, and having done so, break free from this unquestioning faith in these so-called scriptures. Scripture is not a compilation of a false belief, it is a manifestation of the truth. I regard the sayings of the sages, the seers of truth, as sacred. I deeply revere the voice of Mahavir since it touches the soul and is the ultimate and unchanging truth. Hmvever, I do not hold as scripture the books written in the name of the Realised Ones, as they are bereft of any speck of spiritual awareness, and are devoid of the actual experience of the beautiful, the true and the good. I have an unshakeable faith in Mahavir, and my heart is filled with reverence for the truth-seeing sages. This faith, this veneration becomes more powerful and more intense the more it reaches the depths of reflection. Even today, I see that supreme light within me and once again I dedicate my heart completely to it. Mahavir is a pillar of light to me, and the brilliance of his words penetrates and illumines every aspect of my being. In the light of my own reasoning I can clearly see in the scriptures that which is, and that which is not, the voice of a Tirthankar.Words which kindle in our hearts the flame of truth, awaken our slumbering godhead, and expand our inner consciousness to an allpermeating and all-powerful form, can only be the words of the Realised Ones. The vibrancy of the Tirthanakar's voice is attuned to the pace of the soul's progress; it has nothing to do with the course of the stars and the satellites, the depths of rivers and streams, or the greater or lesser heights of mountains of gold and silver. The voice of the seers represents an all-encompassing friendship and a universal consciousness. There are no notes in it of class conflict, cast antipathy, or false fantasies. Neither science, nor experiment can ever challenge the eternal truth that echoes in the voice of the Realised Ones. No genuine seeker after the truth can ever negate the teachings of the Venerated Ones. However, we should not remain so entrenched in our ignorance; we should not believe that everything which passes in the name of scripture, is indeed the indubitable voice of the Supreme Ones, and that every word written in these texts is the gospel truth. To stamp every compilation written in Prakrit, or Ardha-Magadhi with the seal of Mahavir, is not a reflection of true devotion. If we are true devotees, true believers, we need to free ourselves from this tendency; we must understand that any thought, factual information or expression that pertains to research and the analysis of the material world, and can also be disproved by empirical evidence, is not a divine revelation, and we cannot recognise it as a scripture either. It may be a collection, a composition, or literature created or compiled by Acharyas, but it cannot be scripture.

----------------------------------------------------- Source : "The Jains Through Time" Published By : Veerayatan U. K. The Wentworth, Pinewood Close, Oxhey Drive South ----------------------------------------------------- Mail to : Ahimsa Foundation |

|